Collapse - Part 1/5: Denial

Why no one wants to talk about doom and gloom

Twenty years ago, British Royal Astronomer and bestselling author Martin Rees gave me a copy of his book Our Final Century. The title says it all.

In what was presumably a merciful attempt to spare me from falling into despair so early in life, he scribbled a question mark at the end of the title and added:

“Jan/ In the hope that these gloomy thoughts are as wrong as many of my cosmological stories have turned out to be. All good wishes, Martin”

I remember enjoying the book a lot at the time. I appreciated his crystal-clear writing and was intellectually tickled by the complexities of the issues.

However, I was not emotionally affected in any meaningful way, and I soon resumed my hedonistic lifestyle and pedestrian family life, somehow unperturbed by the devastating prognosis of our imminent future I had just read an entire book about.

Taken together with the rest of our predicaments, our baked-in climate change has already enshrined our collective doom, an indisputable fact almost no one recognises.

Frankly, I exhibited the very same response most anyone has to such cautioning: it just didn't register. It rarely does, and there are plenty of reasons why.

First and foremost, to be receptive to warnings about distant threats, one cannot be consumed by attending a more important need in Maslow's hierarchy. That's a solid chunk of the world population lost to the message right there. Ain't nobody got time for that.

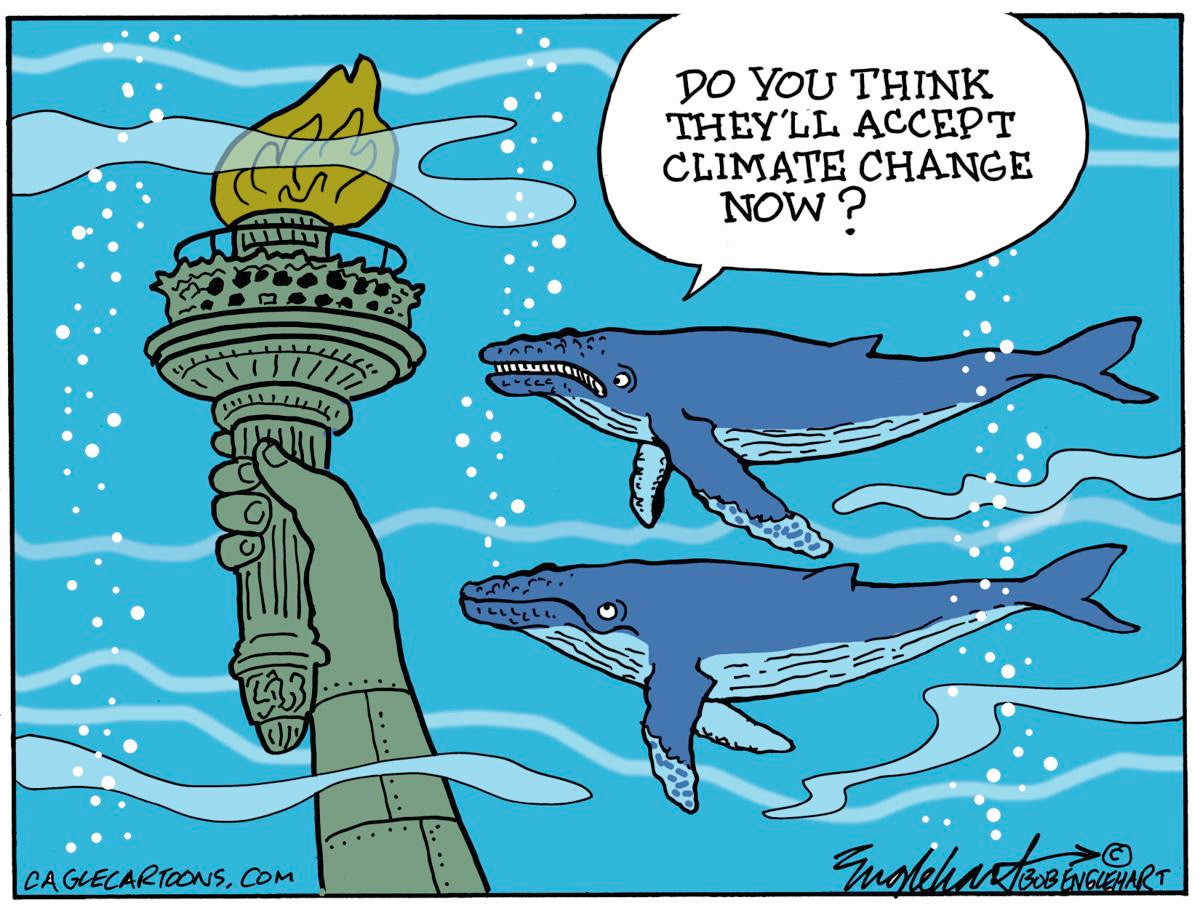

Let's take the threat of climate change, which features in Martin’s book, as an example — though, of course, the word “threat” is a grand misnomer. Taken together with the rest of our predicaments, our baked-in climate change has already enshrined our collective doom, an indisputable fact almost no one recognises.

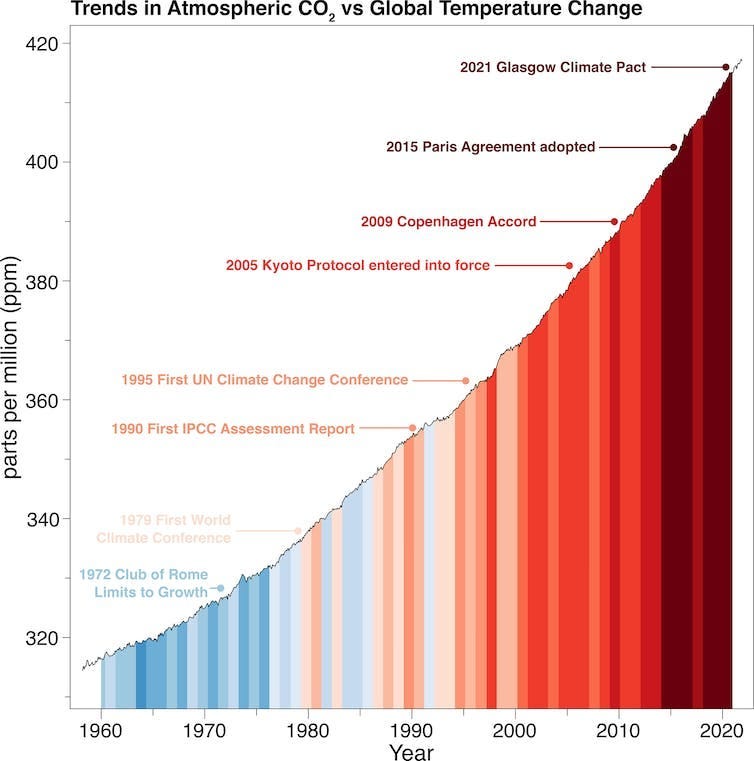

The notion that we can’t enjoy infinite growth on a finite planet entered public awareness in a big way in 1972 with the publication of Limits to Growth. But did the Merchants of Doubt, Reaganite policies, and Thatcherism immediately bulldoze that issue in the name of making rich people richer? You betcha.

William R. Catton Jr’s seminal work Overshoot (1980) plainly stated some hard facts about the ecological overshoot of human populations that we didn’t feel like believing. So we didn’t.

You see, the human mind is equipped with a deflector shield designed to help us ignore inconvenient truths. From a veritable slew of cognitive biases to belongingness to short-sightedness and our insatiable greed, there are countless major obstacles to rational reactions and prudent preparedness against threats of extinction. Game theory, conspicuous consumerism, and black box algorithms stealing our focus then do theirs to seal our fate.

Apart from our hardwired psychological faults, perpetually spreading ideological mind viruses such as creationism and classical economic theory also yield total cognitive protection from embracing an honest relationship with reality. As it is impossible for people to simultaneously hold two conflicting world views in their mind, they find themselves unable to abandon the first, indoctrinated one because that would entail admitting they’d been wrong all along - and we really don’t like doing that. And so they don’t change their mind even when confronted with gainsaying evidence. That one's called cognitive dissonance, one of the biggies.

It's also just hard to know very much about the world, you know? In our overly specialised world, practically everything is on a need-to-know basis — and let’s face it, not much insight is needed to slave away at our bullshit jobs.

One can quite happily gallivant around believing in silly things such as angels, UFOs, the comforting thought of an afterlife, and Flat Earth, without a shred of concrete evidence. Some of these delusions are actually very profitable, for Darwinistic reasons: at the group selection level, communities bound by religious ideologies traditionally outlive secular ones by a factor of four, the latter being too busy arguing amongst themselves.

It turns out that banding together to go “LA-LA-LA, WE CAN’T HEAR YOU” and bonking people on the head is quite advantageous for propagating your tribe, which is precisely why cognitive dissonance has survived evolution so well (so far). After all, war determines who is left, not who is right.

Other psychological deflector shield components that inconvenient truths must penetrate are various forms of denial: literal (it's not happening), interpretive (it's not our fault), and implicative — that is, not accepting what must be done, let alone finding the strength and courage do it, or indeed any way to escape our locked-in system of cancerous Capitalistic societies and Moloch, the Demon of game theory that traps us time and time again in neigh-unsolvable problems such as The Tragedy of the Commons and Freerider Problems, the Achilles heel of Marxism.

Moreover, penetration of the deflector shield requires, in the case of climate change, a penchant for abstract thought in the recipient: the ability to extend a graph line into the future and grasp the consequences, decent in a curiously small portion of the population (and such people are not at all appreciated by the rest).

Most people are sensory types who look out the window and observe that the weather seems rather nice, so all must be well — a useful assessment skill they honed for countless generations way back on the savannah when invisible things such as CO2 levels, microplastics, and forever chemicals weren’t, you know, a thing.

“One of the greatest shortcomings of the human race is its inability to comprehend the exponential function.” - Albert Bartlett

Perhaps if we’d retained a strong connection with the natural world, we’d care more about it.

Sadly, our caring has dissipated from our cultures and peoples ever since the necessary abandonment of animism around the time of the invention of the plough — one can’t very well beat an animal one worships, after all — or, perhaps more accurately, exterminated via the genocide of countless Indigenous peoples, most of whom were a helluva lot wiser than the greedy, power-hungry savages that invaded and conquered their worlds.

Moral philosophy is hard, yo. We’re not wired for it.

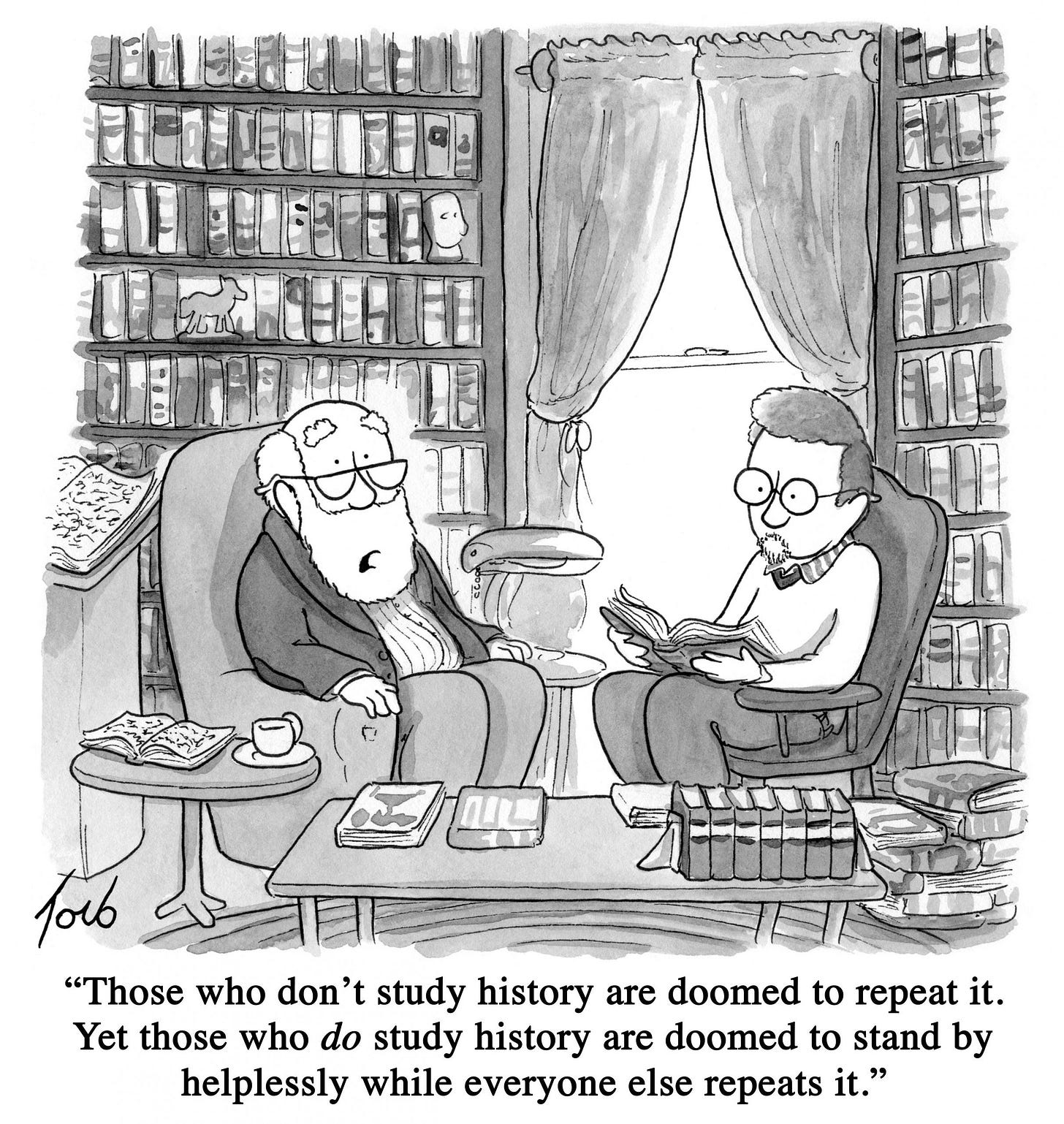

The very few who do see the whole, devastating truth about climate change feel utterly helpless, desperately lonely, and surrounded by sheeple. When committing the faux pas of mentioning it, they immediately run into the social taboos of being a downer and are effectively ostracised.

In the case of scientists and activists, Big Oil can’t afford them to speak any sense, and so crushes them with ad hominem attacks. Abuse and death threats from blind & vile human beings stymie them into cowering submission, and morally bankrupt denialist judges throw them in jail for years.

Their spirits crumble, they sensibly forego having children to prevent adding to the problem of overpopulation as well as to spare the unborn from experiencing the coming hellscape, and eventually end up huddling together in small hushed groups over sad half-pints, lamenting about what might have been.

Ignoring evidence-based conclusions of impending doom is a maladaptive strategy so suicidal that it can fairly be called lunacy.

Veganism is a no-brainer honourable moral choice and is, therefore, one of the more commonly adopted ones. However, it's typically driven by sympathy for the factory farm animals we torture and slaughter by the trillions more than the uncommon knowledge that one pound of beef takes 5000 litres of increasingly precious freshwater to produce.

(Un)fortunately, The Meat Paradox takes care of those sympathies for most people, enabling them to continue gobbling down flesh as if it's somehow okay. I'm not throwing stones here — I'm one of them, which serves to hammer down the point I just made.

Our rational minds are merely press secretaries for the primitive emotions that actually decide our actions, making up excuses for them post-factum, something Buddha figured out 25 centuries ago and science has since corroborated. But don’t feed bad. Moral philosophy is hard, yo. We’re not wired for it.

What we are wired to do is be behaviorally dominated by our reptile and mammalian brains - heck, even our gut bacteria have a controlling vote.

Our very minds are a fundamental cornerstone of our unavoidable demise.

Ugh, it's getting dark, I know. If you're still with me, please read on. We’re almost done for today.

Ignoring evidence-based conclusions of impending doom is a maladaptive strategy so suicidal that it can fairly be called lunacy. Tragically, it's just human nature. We did not evolve to predict and avoid it, as evidenced by the empirical fact that every single civilisation we’ve had so far has failed.

Theoretically, we could have built a utopia. We did have the means.

But that would have required immense wisdom, self-restraint, and compassion for each other at a level far beyond our primitive capabilities. If everyone loved each other, the world’s problems would never have arisen in the first place (cue the eye-rolls).

Unfortunately, the ancient traits of tribalism and xenophobia weren’t stamped out in time to foster the cooperation needed to avoid our collective demise.

In the fight between platitudes and ecological realities there can, in the end, be only one winner.

We shouldn't feel particularly ashamed. It’s the way it goes for all life in the Universe (evidently), thanks to how The Maximum Power Principle (basically, that limitless greedy behaviour is inevitable among self-organising organisms) leads to Malthusian traps proportional to our size and power, ultimately answering The Fermi Paradox via a Great Filter. Ultimately, survival of the fittest culminates with survival of none, each and every time. We won’t realise we’re all in it together until it’s already too late.

But never mind that we are about to extinguish the only “intelligent” life we know of in the entire Universe; let's get back to our fragile mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam and its so-called Homo Economicus, so very busy congratulating himself for inventing stock markets and nation-states and cryptocurrencies out of thin air, entirely too clever for his own good.

It truly is fascinating how we simply believe what we want to believe, imagining that our laughably primitive models of the world even remotely represent actual reality.

“People’s opinions are mainly designed to make them feel comfortable; truth, for most people, is a secondary consideration.” — Bertrand Russell

But then, that’s what politics is all about, isn’t it: Bending reality to satisfy our primal cravings, however morally defensible or attainable or sustainable they may or may not be. It invariably leads to societal collapse as we run head-first into the hard truths we refuse to respect. In the fight between platitudes and ecological realities there can, in the end, be only one winner.

Now, countless people have arrived at this conclusion before me, so to be clear, I'm not exhibiting an ounce of original thought by echoing the gist of it.

Late psychologist and Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman saw it when he, while slipping into an end-of-life depression, despairingly opined that we are simply not mentally equipped to handle the challenges of climate change. The brilliant sociobiologist E. O. Wilson, of course, nailed it long ago when he said:

“The real problem of humanity is the following: We have Palaeolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology.” — E. O. Wilson

I did, however, finally find a moment to pay them some actual attention and have now, at long last, become Collapse-Aware.

But despair not, my friend. For you, we will end on a comforting note.

You will now return to your life full of stuff you’d rather do. This blog will rapidly dissipate from your mind, which is busy protecting you, as it has always done, from truths too heavy to bear.

I’m sure it’ll be fine.

Here, have a cookie.

If you enjoyed this and would like others to also notice it, please like or share it. It's the only way it gets seen more. This is a free blog. Thank you.Part 2 of 5: Depression

Last year a series of unfortunate events plunged me back into a recurring depression, and I found myself, once again, drowning in overwhelming sadness and crippling melancholy.

Calm and well written truth. It's incredibly isolating to be collapse aware. At least, this online connections provide an outlet that many of us don't have in our "real" lives.

I really enjoyed reading this post and can already think of a few people to share it with. It's clever without being pretentious, and explains our current reality by leaning on philosophy and science. It gets really interesting when you start exploring behavioural psychology, universal laws and other principles that help us realise why we're in this mess. My favourite parts are when the tone suddenly changes from serious to sarcastic. A little bit of dark humour will be needed — I think— if we're ever going to make it through! Thanks for shedding a light on this issue. We all need to understand it way better than we currently do.